Only Gandalf can protect Europe from the Unitary Patent

Now that, despite all legal, political and economic issues, the European Parliament has approved the regulation on the unitary patent, just as anticipated, it is time to move away from the legislative battle. The unitary patent has still a long way to go before becoming applicable. It is likely that it will be nothing more than a stillborn child. Meanwhile, the threat is hovering over European innovation and growth. It is time now to see whether and how Gandalf's magical powers can overcome the dark forces of Mordor.

Now that, despite all legal, political and economic issues, the European Parliament has approved the regulation on the unitary patent, just as anticipated, it is time to move away from the legislative battle. The unitary patent has still a long way to go before becoming applicable. It is likely that it will be nothing more than a stillborn child. Meanwhile, the threat is hovering over European innovation and growth. It is time now to see whether and how Gandalf's magical powers can overcome the dark forces of Mordor.

Hobbit Introduction

I’m a hobbit. I’m a hobbit with a hobby: I write and use software. And I love to enjoy the capabilities software and the Internet bring in order to change the balance of powers deciding who can express her opinion. But software patents are threatening my hobby! So I have a new hobby: preventing software patents from preventing these capabilities to be fully available to everyone. I’ve been highly involved, from 2003 to 2005, in the war to defeat the European Union (EU) directive on software patents. This war has been won. Then I’ve fought against plans from the patent microcosm to install a specialised patent court to enforce software patents. This war has been won, twice. The first time when the plan called EPLA, drafted inside the European Patent Office (EPO), was rejected by the European Parliament (EP). The second time when the so-called European and European Union Patent Court (EEUPC) proposed by the Council of the EU was smashed by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

I’m a hobbit. I’m a hobbit with a hobby: I write and use software. And I love to enjoy the capabilities software and the Internet bring in order to change the balance of powers deciding who can express her opinion. But software patents are threatening my hobby! So I have a new hobby: preventing software patents from preventing these capabilities to be fully available to everyone. I’ve been highly involved, from 2003 to 2005, in the war to defeat the European Union (EU) directive on software patents. This war has been won. Then I’ve fought against plans from the patent microcosm to install a specialised patent court to enforce software patents. This war has been won, twice. The first time when the plan called EPLA, drafted inside the European Patent Office (EPO), was rejected by the European Parliament (EP). The second time when the so-called European and European Union Patent Court (EEUPC) proposed by the Council of the EU was smashed by the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU).

My interest in the unitary patent package was twofold. First, there was a huge concern with regard to the installation of a more powerful patent regime, obviously imbalanced in favour of patentees and under the sole governance of the patent microcosm, i.e. granted by the European Patent Office (EPO), administered by a so-called “Select Committee” of the Administrative Council of the European Patent Organisation (EPOrg), mostly composed by heads of national patent offices, and enforced by a specialised patent court, staffed with legal patent judges, along with so-called “technical patent judges“ who are engineers with a basic training in patent law, with nothing preventing all of these judges to be chosen among members of the EPO. In short, everything in the unitary patent package was made up to waive patent issues to the patent microcosm. Since the patentability of software was the result of case law developed by the EPO and followed progressively by specialised patent judges from national patent courts, such an isolation of the unitary patent in the hands of the patent microcosm was likely to rubber-stamp EPO practices to consider software patents valid. Such an anticipation had solid grounds in the comparable specialised patent court in the United States, the Court of Appeal of the Federal Circuit (CAFC), which has demonstrated since its installation 30 years ago to have developed a capture of the patent system with a bias in favour of patentees and an ever growing extension of patentability.

Second, I’ve seen the regulation on the unitary patent as an opportunity for the EU legislator to introduce clear rules excluding software from patentability. As said, it was the EPO in the first place who circumvented the exclusion of computer programs from patentability as written down in the European Patent Convention (EPC). The European Parliament has already refused twice, in 2003 and 2005, to enshrined EPO practice in EU law. But since no EU law was passed, the EPO has continued to grant tens of thousands of software patents. As the quasi-judiciary highest authority of the EPO, the Enlarged Board of Appeals, has stated itself: “When judiciary-driven legal development meets its limits, it is time for the legislator to take over”. The regulation on the unitary patent was such an opportunity for the EU legislator to “take over”. Moreover, since this project was initiated as a way for the EU to install a genuine EU patent, defining clearly substantive patent law, including patentability rules, should have been a priority.

These are the reasons why I’ve built up the unitary-patent.eu website and been highly involved in the monitoring of the unitary patent regulation.

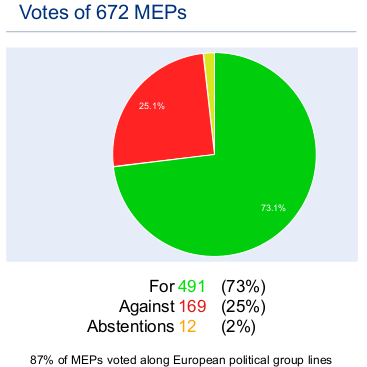

What has happened? Dwarves from European Parliament shirk responsibilities

The legislative stage has been a failure. On Tuesday December 11th, 2012, the European Parliament voted for the unitary patent regulation, rejecting all amendments we had proposed in order to create a genuine EU patent, which would have been fully governed by EU law, and would have clearly excluded software patents. This was a clear failure. The reason is simple: despite having support from more than 600 IT firms, despite raising issues confirmed by academics, despite critics, at the eleventh hour, of major European economic players, we have failed to raise an army of citizens, which could have patrolled the Brussels corridors. In this fight, we were just a bunch of hobbits, and this was not enough to convince parliamentary dwarves. Now, here are the details of how and why we have failed.

The legislative stage has been a failure. On Tuesday December 11th, 2012, the European Parliament voted for the unitary patent regulation, rejecting all amendments we had proposed in order to create a genuine EU patent, which would have been fully governed by EU law, and would have clearly excluded software patents. This was a clear failure. The reason is simple: despite having support from more than 600 IT firms, despite raising issues confirmed by academics, despite critics, at the eleventh hour, of major European economic players, we have failed to raise an army of citizens, which could have patrolled the Brussels corridors. In this fight, we were just a bunch of hobbits, and this was not enough to convince parliamentary dwarves. Now, here are the details of how and why we have failed.

Failure to ban software patents

Every deputy, every government official we have met with my hobbit friends, has confirmed her opposition to software patents. For instance, take the report of the French parliamentary Committee on EU Affairs, which had invited me to a hearing, which states (our translation): “The patentability of software is inconceivable because they derive from mathematical formulas: allowing to patent software amounts actually to allow the patenting, for example, of the formula E = mc2, with binding effects on research. It would undermine the very foundations of knowledge sharing and the possibility of innovation.”

Every deputy, every government official we have met with my hobbit friends, has confirmed her opposition to software patents. For instance, take the report of the French parliamentary Committee on EU Affairs, which had invited me to a hearing, which states (our translation): “The patentability of software is inconceivable because they derive from mathematical formulas: allowing to patent software amounts actually to allow the patenting, for example, of the formula E = mc2, with binding effects on research. It would undermine the very foundations of knowledge sharing and the possibility of innovation.”

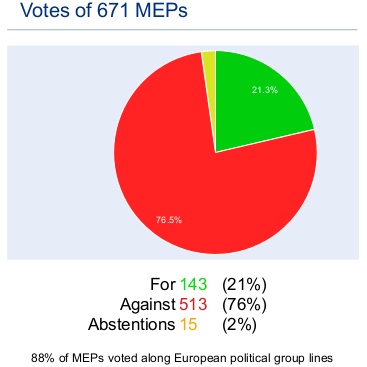

Despite this, the amendment we have proposed to clearly exclude software patents was overwhelmingy rejected by the European Parliament: about 3/4 of parliamentary dwarves voted against this amendment, as shown in the above chart. But how come there is such a contradiction between words and actions? One answer can be found in the memorandum prepared by the rapporteur, the German socialist Bernhard RAPKAY, for the socialist group of the European Parliament. In this 13 pages background note, a section is dedicated to software patents. It is worth reading in its entirety (italics, bold, underline emphasis and typos in the original):

SOFTWARE PATENTS - myths and facts

1. We are not granting patents on software via this regulation that only establishes unitary patent protection in the 25 Member States.

2. The Computer Programmes Directive was a sectoral measure, the Rapkay report is not about revising the Computer Programmes Directive.

3. In 2005, the European Parliament rejected the proposed computer-implemented inventions patent directive. This EP position of 2005 is by no mean the object of the Unittary – sic – Patent Regulation in any kind.

APPLE vs SAMSUNG was submitted to USPTO- SAN JOSE COURT and the Japanese patent office. We want the unitary title to be able to compete with USPTO and JPO. Besides, the case is not only about scrolling and sizing but trade dress ("your tablet looks like mine") and industrial designs.

4. We uphold all the limitations to patentability set in the acquis transposed in national law (biotech, the research exception, the pharmacy, experimentation exception are in the text). Moreover we have persuaded the Council to insert in the final text of the regulation, in Recital 10 – sic, it is obviously recital 11 –, the right of the Union to come forward with other sectoral measures that could further limit or enlarge patentability, as per Union’s conferred powers- redline in our negotiation

5. The ref. to 2009/24/EC, in particular Art. 5 and 6 is in the UPC text and binding on Court, the primacy of the EU law is spelled out, Union law is mentioned as source of substantive law in Chapter III of the UPC Agreement

6. Also to bear in mind that, unlike US or Australian patent law, Art. 52 of the European Patent Convention forbids patents on: "schemes, rules and methods for performing mental acts, playing games or doing business, and programs for computers;

And now, let’s just take Mr RAPKAY’s last assertion. Like everything that is said here, it is not controversial. The problem is that this section entitled Myths and Facts states some actual facts and omits many others, ending up in a complete myth. It is true that paragraph 2 of Article 52 EPC excludes software and everything listed above – mathematical methods and presentations of information could also have been included – but to the extent, as written down in the next paragraph 3 of the same Art. 52 EPC, that the patent relates to them as such. This as such clause has been interpreted by the EPO to mean “that has no technical effects”. Technical effects, as interpreted by the EPO, includes data retrieval, reaction to a user input, or even “writing using pen and paper” (sic!). This has allowed the EPO to circumvent the exclusion of software from patentability and to actually grant already tens of thousands of software patents.

So the fact is that software patents are actually granted and enforced in Europe and the problems they generate are only compounded by the unitary patent project. I’ll explain below in detail how the threats posed by software patents are exacerbated with the unitary patent. Suffice to say for now with regards to Mr RAPKAY’s myth that the San Jose case between Apple and Samsung he refers to does include some software patents, which are actually also granted in Europe by the EPO, and are found valid by some European courts, resulting in the exclusion of some products from some national markets. Would these patents be unitary patents, the whole EU market, except Spain and Italy, would be affected.

More important, the fact is that in his first three assertions, Mr RAPKAY denies the fact that the regulation on the unitary patent, as an instrument to create an EU patent, should have addressed issues of substantive patent law that have been identified to question the initial goal of the patent system to allegedly foster innovation. Software patents are one of these issues. It is a pity to encourage the EU legislator to not take over.

It is also a pity to rely on such poor arguments as the exception of decompilation – Arts 5 & 6 of Directive 2009/24/EC on the legal protection of computer programs –, under some conditions, as a limitation to patentability, while such a limited exception has never been used, as far as we know, for defence in a case of patent infringement. As for the future rights of the Union to regulate on patentability, it is a pity to rely on a mere non-binding recital, requiring that the Commission includes some proposals in a non-binding report. And it becomes a crying shame to resort to a mere declaration of the primacy of EU law, while everything in the unitary patent project has been made to side-step EU law, as I’m gonna explain in the next section.

But that’s how 3/4 of parliamentary dwarves were convinced that the unitary patent regulation was not the place to address software patents, on account of their existing ban in Europe. It takes a lot of nerves to assert this myth as a fact. Nevertheless Mr RAPKAY has unfortunately won, to the detriment of hundreds of IT firms who have asked for software patents to be specifically addressed by the unitary patent regulation.

Failure to create an EU patent

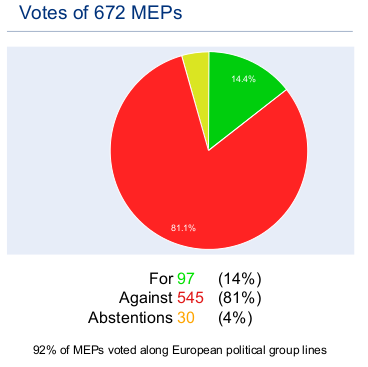

It is with the same kind of deceiving arguments that the majority of parliamentary dwarves was convinced to vote for something completely different from a genuine EU patent. The “new regime will cut the cost of an EU patent by up to 80%” claims the press release of the European Parliament. How could such a figure be estimated while the level of renewal fees for unitary patents has not been decided yet? It is still unknown. But with such cost savings, opposing the creation of an EU patent was not an option any more, as shown in Questions and Answers published on the European Parliament website one week before the vote. This page cunningly describes how much the EU needs an EU patent. The problem is that an amendment that would have guaranteed that the unitary patent was really, as expected, an autonomous EU patent, fully governed by EU law, has been rejected by 4/5 of the parliamentary dwarves. The reason is that they believed that the proposal for a unitary patent already matched all these expectations. And indeed this is what can be understood by reading press releases or official informations, as pointed out above. Unfortunately, the voted regulation on the unitary patent does not create any EU patent.

It is with the same kind of deceiving arguments that the majority of parliamentary dwarves was convinced to vote for something completely different from a genuine EU patent. The “new regime will cut the cost of an EU patent by up to 80%” claims the press release of the European Parliament. How could such a figure be estimated while the level of renewal fees for unitary patents has not been decided yet? It is still unknown. But with such cost savings, opposing the creation of an EU patent was not an option any more, as shown in Questions and Answers published on the European Parliament website one week before the vote. This page cunningly describes how much the EU needs an EU patent. The problem is that an amendment that would have guaranteed that the unitary patent was really, as expected, an autonomous EU patent, fully governed by EU law, has been rejected by 4/5 of the parliamentary dwarves. The reason is that they believed that the proposal for a unitary patent already matched all these expectations. And indeed this is what can be understood by reading press releases or official informations, as pointed out above. Unfortunately, the voted regulation on the unitary patent does not create any EU patent.

This is already obvious from the actual name of the unitary patent: European patent with unitary effect. To be sure, Article 2 states that “‘European patent’ means a patent granted by the European Patent Office (hereinafter ‘EPO’) under the rules and procedures laid down in the EPC”, and therefore “‘European patent with unitary effect’ means a European patent which benefits from unitary effect in the participating Member States by virtue of this Regulation;”. So, at the grant stage, the unitary patent is not different from classic European patents. It is granted by the same non-EU agency: the EPO. And it is governed by the same international non-EU law: the EPC. This means in particular that patentability rules are to be found in the EPC and not in EU law. Then, recording the unitary effect is delegated to the EPO. The administration is also left outside the EU since the unitary patent regulation has entrusted a “Select committee” of the EPO with, amongst other tasks, fixing the level of renewal fees for unitary patents and how these fees are to be redistributed to the EPO itself as well as to participating Member States. This Select committee is likely to be staffed, as the current Administrative Council, mostly by heads of national patent offices. This is very worrying, because the objective of the EPO and of national patent offices is not to fix and collect fees for the benefit of society and economy as large, but to reach at least a balanced budget, or even to make profits. When additional revenue is to be drawn from renewal fees of granted patents, a bias toward granting rather than rejecting patent applications is introduced. Patent offices are indeed less similar to public agencies than to for-profit organisations acting for the benefit of their clients. And clients of patent offices are patent applicants who want to have their applications granted. No doubt that this bias is at the origin of the expansion of the scope of patentability to new fields, like life forms, or software. And the unitary patent regulation does nothing to change this incentive to grant more patents.

But the EU is also set aside at the post-grant stage. Indeed unitary patents, as objects of property, are to be governed by national laws, according to patent owners’ residence, and by German law for unitary patents held by non-EU residents. As for any usual countervailing rights in patent law – exceptions and limitations (such as for private non-commercial usage, for research purpose, for surgical acts, for seeders and breeders, etc.), prior user-rights, compulsory licenses, etc. –, they are all defined outside EU law, but rather in national laws, sometimes harmonised by international conventions.

This is very important with regard to the exclusive competence of the newly created Unified Patent Court (UPC) in validity and infringement proceedings related to unitary patents. The UPC may, and sometimes shall, refer some issues to the CJEU for preliminary rulings. But these referrals are restricted to the interpretation of EU law. This means that the CJEU can review issues about the mere registration of the “unitary effect”, i.e. when an usual EPO patent is asked by its holder to be registered as a unitary patent. The CJEU can also review decisions concerning biotechnologies and supplementary protection certificates, since both were regulated years ago by the EU, and are therefore part of EU law. But that’s all! The CJEU won’t be competent to review granting or rejecting decisions made by the EPO. Moreover, as we are going to see further below, it won’t be competent to rule on counterfeiting of unitary patents. And the CJEU won’t be competent for any countervailing rights: exceptions and limitations, prior user-rights, compulsory licences, etc.

So what is left to EU is so cosmetic that it is hard to interpret the unitary patent as a genuine EU patent. Nevertheless, when proposed to entrench the unitary patent in EU law, 4/5 of parliamentary dwarves have trusted the Commission, the Council, and the (ir)responsible dwarf for each main political group of the European Parliament, and have rejected the amendment. This means that, except for the Green/EFA and GUE-NGL groups, the European Parliament has indeed refused to create an EU patent.

Failure to comply with EU treaties

Side-stepping the EU from almost every part of the unitary patent is one thing. But doing so does not comply with the legal basis of the regulation, which explicitly authorises the EU to create an EU patent. This should already have prevented parliamentary dwarves from voting for an illegal text. But with the last so-called compromise proposed by the Cyprus presidency of the Council, they could not have ignored any more that the regulation was indeed subject to very strong legal concerns. Indeed, since the (ir)responsible dwarf Committee has refused that the confirmation of this illegality from the legal services be formally written down, my hobbit friends and I wrote to all parliamentary dwarves, warning them about lies of the rapporteur, Bernard RAPKAY, about the very legality of this “Cyprus compromise”, as questioned by the legal services of the European Parliament:

Side-stepping the EU from almost every part of the unitary patent is one thing. But doing so does not comply with the legal basis of the regulation, which explicitly authorises the EU to create an EU patent. This should already have prevented parliamentary dwarves from voting for an illegal text. But with the last so-called compromise proposed by the Cyprus presidency of the Council, they could not have ignored any more that the regulation was indeed subject to very strong legal concerns. Indeed, since the (ir)responsible dwarf Committee has refused that the confirmation of this illegality from the legal services be formally written down, my hobbit friends and I wrote to all parliamentary dwarves, warning them about lies of the rapporteur, Bernard RAPKAY, about the very legality of this “Cyprus compromise”, as questioned by the legal services of the European Parliament:

Moreover, we’d like to point you that, contrary to the assertion by rapporteur RAPKAY that the legal services of the European Parliament have “put forward supportive arguments for that compromise”, the video recording shows that they actually said: “this compromise text has not ended all legal concerns”, adding that it was a “problematic situation”. Therefore you’re about to vote for a text which does not install a genuine single EU patent, and whose legality is at best uncertain.

But they didn’t even need to hear our hobbit warnings. Parliamentary dwarves knew already that what was proposed by the Council was an “emasculation” of the text, which then “will go straight to the European Court of Justice”. This is how they have rightfully judged the proposal from the European Council to move Articles 6 to 8 out from the unitary patent regulation to the UPC international agreement. These three articles were defining the uniform protection conferred by unitary patents, by formalising direct and indirect infringements to unitary patents and exceptions thereof. Moving these outside the unitary patent regulation would have indeed voided it from anything substantive to regulate. Consequently, the CJEU wouldn’t be competent to rule on counterfeiting of unitary patents and exceptions thereof.

The last ”Cyprus compromise”, that we have recognised being a real troll, does nothing else but adding in the unitary patent regulation a mere restatement that the protection conferred by unitary patents shall be uniform, but referring to national laws, as harmonised by the UPC agreement, for the very definition of this protection. As headlined by Intellectual Asset Management (IAM) magazine: “When it comes to the EU patent it seems that what was intolerable yesterday is fine today“. Just to be sure, the British parliamentary committee responsible for this dossier concluded in April 2012 about the planned complete deletion of Articles 6 to 8: “There is, however, in our opinion an inevitability to their inclusion. Whilst the arguments of Professors Kraßer and Jacob strike us as right as a matter of patent law, the counter-arguments of the Commission on what is required to implement Article 118 TFEU seem to reflect the firm views of the EU institutions, including the Court of Justice, as a matter of EU law. This calls into question whether incorporating a unitary patent regime within the EU will ever be practicable.” But a document published a couple of days after the European Parliament’s vote states that, at a meeting held a week earlier, the same committee approved the following UK Government’s position: “the Government is sure that, compared to no Article at all, [the ‘Cyprus compromise’] ‘increases the risk of references to the [CJEU] on matters of substantive law of patent infringement by no more than a negligible amount (one so low that it can in practice be ignored).‘”

Another consequence of this Cyprus troll is that if the European Parliament decides one of these days to adjust an existing exception (such as for seeders who cannot sell their products if infringing any patent), or to vote for a new exception (such as for developing/using software on a generally used computing hardware), the European Commission can propose this to EP’s and Council’s vote in order to put it into EU law. But it is doubtful that this will bind the UPC. Changes to the UPC agreement, even to comply with a new EU law, are to be decided by government representatives – who are very likely to be chosen among heads of national patent offices – with one vote per country and a right of veto. To be fair, the UPC agreement also states that the Unified Patent Court shall respect the primacy of EU law. But what law will specialised patent judges apply when they have to rule on a new exception, voted into EU law but blocked from being written down in the UPC agreement by the veto of at least one head of a national patent office? This means that the European Parliament has indeed waived a lot of its powers to the patent microcosm.

But this also means, that 3/4 of the parliamentary dwarves have done so in clear contravention of the competences bestowed on them by the EU treaties.

What’s next? Gandalf’s powers

In theory, the Commission, as the executive branch of the EU, is assumed to be the guardian of the Treaties. But for the unitary patent regulation, the Commission introduced a proposal which was not compliant with its legal basis in the Treaties to begin with. Then, the governments of EU Member States, acting as co-legislators for the EU in the Council, but representing the executive of their respective country, have exacerbate this non-compliance by eviscerating the regulation from almost any substantive provision. The other co-legislator, the European Parliament, has surrendered and chosen to drop any resistance against such obvious illegalities. The reason is likely to be, as anticipated in our analysis of the legal basis of the unitary patent regulation, that they’ve chosen to “stick to the current proposal despite its questionable legal basis, with the hope that it won’t ever be asserted by the CJEU”.

In theory, the Commission, as the executive branch of the EU, is assumed to be the guardian of the Treaties. But for the unitary patent regulation, the Commission introduced a proposal which was not compliant with its legal basis in the Treaties to begin with. Then, the governments of EU Member States, acting as co-legislators for the EU in the Council, but representing the executive of their respective country, have exacerbate this non-compliance by eviscerating the regulation from almost any substantive provision. The other co-legislator, the European Parliament, has surrendered and chosen to drop any resistance against such obvious illegalities. The reason is likely to be, as anticipated in our analysis of the legal basis of the unitary patent regulation, that they’ve chosen to “stick to the current proposal despite its questionable legal basis, with the hope that it won’t ever be asserted by the CJEU”.

Then, in order to prevent the European patent system from being fully captured by the patent microcosm, the only remaining hope lies with some kind of powerful wizard. Someone or something whose powers are at least as mighty as the legislative and executive arms of the EU. Of course, from Aristotle to Locke and Montesquieu, the model of the separation of powers has provided for such a third power to balance the legislature and the executive, namely: the judiciary. And in the European Union, the judicial authority is vested in the Court of Justice of the European Union (CJEU). Endowed with Gandalf’s tremendous powers, the CJEU can indeed prevent disasters that the unitary patent, as voted by the EU legislator, would cause. And since, as we have seen, the whole unitary patent project has tried to exclude the CJEU as far as possible, despite Gandalf’s previous admonitions, he has every reason for not being happy with what was voted.

Union’s fundamentals

The first opportunity for the CJEU to use its powers over the unitary patent regulation lies with a ruling, expected in the beginning of 2013, on the legality of the procedure which was chosen by the Council and the EP to legislate on this regulation. Arguing from the impossibility to reach within the Council the unanimity required for adoption of language arrangements, the EU decided to use an enhanced cooperation procedure. Such a procedure is provided for by the EU Treaties to allow for differentiated integration. Under some conditions, enhanced cooperation may be used to allow the EU to move forward on some issues, even if some Member States do not yet fulfil all requirements to implement the relevant reforms at the same speed as the other ones. Spain and Italy think that conditions to authorise the enhanced cooperation are not fulfilled for the unitary patent regulation. So, in the summer of 2011, they brought actions for annulment of the enhanced cooperation procedure before the CJEU.

The first opportunity for the CJEU to use its powers over the unitary patent regulation lies with a ruling, expected in the beginning of 2013, on the legality of the procedure which was chosen by the Council and the EP to legislate on this regulation. Arguing from the impossibility to reach within the Council the unanimity required for adoption of language arrangements, the EU decided to use an enhanced cooperation procedure. Such a procedure is provided for by the EU Treaties to allow for differentiated integration. Under some conditions, enhanced cooperation may be used to allow the EU to move forward on some issues, even if some Member States do not yet fulfil all requirements to implement the relevant reforms at the same speed as the other ones. Spain and Italy think that conditions to authorise the enhanced cooperation are not fulfilled for the unitary patent regulation. So, in the summer of 2011, they brought actions for annulment of the enhanced cooperation procedure before the CJEU.

On December 11th, 2012, just a couple of hours before the vote of the EP, Yves Bot, who is one of the Advocates General (AGs), kind of legal advisors for the judges of the CJEU, gave his conclusions that Spanish and Italian recourses should be rejected. It would go beyond the scope of this article to analyse whether the CJEU is likely to follow the AG’s conclusions. We would need to write a thorough legal paper for this. But in order to show you that, from a purely legal point of view, this is at least questionable, let’s just consider a single disputable argument.

One requirement for the EU to legislate according to the enhanced cooperation procedure is that the matter to legislate upon be outside the exclusive competences of the EU. This is one of several kinds of powers that Member States have given the EU. In fields of exclusive competence, the EU and only the EU can legislate. The Member States cannot legislate any more in fields of exclusive competence. Such fields cannot be legislated upon according to the enhanced cooperation procedure. But the Advocate General has stressed that the competence conferred on the EU to create a unitary patent, that is Article 118 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), is explicitly given in “the context of the establishment and functioning of the internal market”. The internal market is not listed in the fields of exclusive competence of the EU, exhaustively defined, according to the AG, in Article 3 TFEU. Rather, the internal market is listed in Article 4 TFEU defining shared competences of the EU – that is, powers that Member States can exercise in so far as the EU has not legislated yet. The enhanced cooperation procedure is allowed in fields of shared competences. Therefore, the AG concluded that the creation of a unitary patent could be legislated upon according to the enhanced cooperation procedure. In other words, according to the AG, it is the place in the EU Treaty where the power to create a unitary patent is written down that makes it fall outside exclusive competences and therefore opens it up to enhanced cooperation.

This is a convincing valuable legal argument. Nevertheless, equally convincing legal arguments can be made, to reach the exact opposite conclusion that the creation of a unitary patent is actually an exclusive competence of the EU. As rightly recalled by the AG, clarifying the sharing of competence between the Union and the Member States was an explicit mandate to the European Convention which was set up to draft the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe, and whose work eventually materialised in the Treaty of Lisbon. But the Advocate General has failed to remark that the same mandate also recognised that “Any consideration of the problem of delimiting competence must take account of this need to find a balance between the demand for some flexibility and the demand for precision in delimitation. Every constitutional system which establishes a federal system or a system with a strong regional component tries to strike this balance in one way or another, but there is no ‘ideal’ system for the delimitation of competence. In all existing constitutional texts – even in those based on a catalogue of powers – grey areas exist and constitutional courts are called on to resolve questions relating to the resultant conflicts of competence."

Therefore, it can perfectly be argued, as done by the European Policies Committee of the Italian Chamber of deputies, that, whatever its place in sections of the TFEU and its reference to the internal market, Article 118.1 TFEU actually defines, by nature, an exclusive competence of the EU. Such an exclusive competence defined by the object and the purpose of the relevant legal basis in the treaties, has indeed be asserted by the same mandate to the European Convention with regard to the setting up of joint bodies such as Europol or Eurojust, which “may be regarded as falling within the exclusive competence of the Union given that this task, by its very nature, cannot be carried out by each Member State acting individually”, adding that “The same applies to the creation and setting up of joint bodies on the basis of the EC Treaty (e.g. Trade Mark Office).“

Moreover it was the conclusion of the Working Group on Complementary Competencies of the European Convention that “areas of exclusive and shared competence [should be] respectively determined in accordance with the criteria developed by the Court [of Justice of the European Union].” One of these criteria, according to this workgroup, is that exclusive competences relate precisely to “matters where it is essential that the Member States do not act by themselves, even if no Union solution can be found”. Indeed, only the Union can create a Union patent. There is no room here for the application of the subsidiarity principle defined in Article 5.3 TFEU: “in areas which do not fall within its exclusive competence, the Union shall act only if and in so far as the objectives of the proposed action cannot be sufficiently achieved by the Member States, either at central level or at regional and local level, but can rather, by reason of the scale or effects of the proposed action, be better achieved at Union level”. The creation of a Union patent, as provided for by Article 118.1 TFEU, cannot be better achieved at Union level than by the Member States. Indeed, it can only been achieved by the Union, as the Advocate General himself has admitted.

As said, the complete development of these arguments would need to be addressed in a legal analysis which is beyond the scope of this article. Suffice to note that there are serious legal reasons to reject the enhanced cooperation procedure – at least as serious as the Advocate General’s arguments to accept it. In such a case, the final decision necessarily has some political grounds, despite the separation of powers. With regard to the enhanced cooperation on the unitary patent, the CJEU will have to eventually decide whether to open up the gates to the enhanced cooperation procedure or to define it in a narrow way in order that this procedure cannot be used for political convenience. Enhanced cooperation has never been really tested. The only case where it has ever been used, in the context of the law applicable to divorce and legal separation, was not a real issue, everybody – participating and non-participating Member States – having agreed to disagree. So the unitary patent is a first test. Authorising enhanced cooperation on the unitary patent would give Member States confidence to use it more often in order to overcome their disunity. Budgetary and financial measures are candidates ready to jump in if the door is opened. But is this really what the Union should be about? Well, this is a political choice. And there is no doubt that the CJEU’s final decision regarding enhanced cooperation on the unitary patent will have a strong impact on this choice.

Another factor in the final decision is that this case is special in that the implementations of the enhanced cooperation, i.e. the unitary patent regulations and the UPC, have been set up rather quickly – despite all unforeseen developments – in a way that can hardly please the CJEU – especially after its strong opinion on the former EEUPC project was expressed. As we have already noted, everything has been done to side-step the EU in general, and the scope of the CJEU review in particular. This is a strange way to reply to its opinion on the EEUPC, which complains that this earlier project would not have given the CJEU the opportunity to guarantee the application and the uniformity of EU Law. Thus, since there are some arguable legal grounds to reject the authorisation for the enhanced cooperation procedure, it might well be that the CJEU eventually decides to put an end to this mess, without waiting for review of the unitary patent regulation itself.

Nullity of the unitary patent package

As much as I wouldn’t bet on one outcome or the other in the opposition before the CJEU with regard to the enhanced cooperation procedure, I have no doubt any more with regard to the unitary patent regulation and the UPC international agreement.

As much as I wouldn’t bet on one outcome or the other in the opposition before the CJEU with regard to the enhanced cooperation procedure, I have no doubt any more with regard to the unitary patent regulation and the UPC international agreement.

At the very moment the Commission has published its proposal for a unitary patent regulation, on April 13, 2011, my first reaction was: “Hey, they don’t want to create an EU patent any more, just the old EPO patent with a mere ‘unitary’ flag! Can they do this?” Then, as any good hobbit, I’ve worked hard to find an answer, digging into tons of legal texts – preparatory works of the EPC, case law of the CJEU, academic papers… The outcome of this research was made available online in early July 2011, in an analysis concluding that there were strong legal reasons to at least question the legality of this proposal. At that time, I just said “at least question the legality” because I hadn’t seen anybody else raise the issues that I had found. After all, I’m just a hobbit, I have no degree in legal matters. But one thing I’ve learnt during my previous fights in legal and legislative battles was that “As in any legal matter, nobody can answer to the substantial issues we’ve raised with 100% of certainty… until the ultimate ruling of the competent jurisdiction – in our case: the Court of Justice of the European Union.” So it was better to be cautious rather than to claim the unerring illegality of the unitary patent regulation.

But as months passed and the unitary patent regulation made its way through the EU legislative process, study after study was published by senior academics, confirming the legal flaws of the unitary patent regulation. In the beginning, academic ents were focusing on other flaws, in the enhanced cooperation procedure, or in the Unified Patent Court, or on the imbalances of the unitary patent system. Fundamental issues we’ve raised were just a portion – still subject to interpretation – of their papers. But more and more, taking into account some papers we have not reported bout yet on the unitary-patent.eu website, and some that are still unpublished, as well as personal conversations with some academic ents, my legal analysis has proven to be true. And even the most prominent patent supporter from the Commission, during a presentation at the EPO just a couple of months before the EP vote, came to the same inescapable conclusion: the unitary patent regulation was not compliant with its legal basis. This means that the very provision in the EU treaties which empowers the EU to legislate on this matter is violated by the regulation. Parliamentary and governmental dwarves have abused their powers! This is a very strong accusation – but one that Gandalf cannot leave unpunished.

It would take another legal paper to collect all legal arguments that have been raised here and there against the legality of the unitary patent regulation. But let’s simply recall simply here the main reasons. The legal basis in the EU treaties gives the EU competence to create, under the EU ordinary legislative procedure, an EU patent providing uniform protection throughout the EU. But, as we’ve seen above, this is not what the unitary patent is about. The unitary patent is presented as a classic EPO patent. In order to do so, the EU regulation is said to constitute an international agreement. This is a total mix of irreconcilable areas of law: public international law and municipal EU law. Moreover, many aspects of the uniform protection have been left out to national laws. And with the Cyprus troll, not a single bit of such uniform protection has been kept under EU law. This means that it is not provided according to the EU ordinary legislative procedure. To be compliant with its legal basis, the unitary patent should have had an autonomous character, meaning that all provisions governing the life of the unitary patent, from its grant to its enforcement or revocation, should have been found in EU law. And this is indeed what was expected, in view of the authorisation given for the enhanced cooperation procedure. At that stage, the unitary patent was presented just like the former project for a Community patent. Therefore, its illegality may be compounded by the fact that it does not even comply with the authorisation for enhanced cooperation.

But the unitary patent regulation is not alone in the so-called “patent package” to exhibit serious legal flaws. There are also solid arguments to challenge the legality of the international agreement on a Unified Patent court (UPC). Here again, it would take a proper legal papers to detail these arguments. But the main point is that UPC is an international agreement concluded between Member States, without the EU being a party. According to Article 3.2 TFEU: “The Union shall also have exclusive competence for the conclusion of an international agreement when its conclusion is provided for in a legislative act of the Union or is necessary to enable the Union to exercise its internal competence, or in so far as its conclusion may affect common rules or alter their scope.” In the context of the UPC, all these three conditions are fulfilled. Article 18 of the unitary patent regulation requires the ratification of the UPC agreement in order to enter into force. It follows from this provision that the conclusion of the UPC agreement, first, is provided for in a legislative act of the Union, and second, is necessary for the exercise of the EU competence to create a unitary patent. Moreover, as it has been assessed by the Commission services, the UPC agreement does affect the Union acquis, and in particular the regulation on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters (the Brussels I Regulation). It could be objected that Art. 3.2 TFEU applies only to external international agreements, that is: to international agreement concluded between the EU and third countries. But in Case C‑370/12 of November 27th, 2012, about the Treaty establishing the European stability mechanism (ESM), the CJEU has interpreted that: “It follows also from that provision that Member States are prohibited from concluding an agreement between themselves which might affect common rules or alter their scope.” The bottom line is that the EU shall have exclusive competence to conclude the UPC agreement. There is no way to consider that the unitary patent regulation could amount to an explicit authorisation for EU to waive its exclusive competence. Therefore, Member States are not authorised to conclude the UPC agreement between themselves.

I could go on with questionable issues, to say the least, that the UPC agreement complies with the CJEU opinion that national courts shouldn’t be deprived of their competences on patent litigations. Or with the blatant differences between the UPC and the Benelux Court, which dwarves have taken as an obviously wrong example to maintain that the UPC agreement complies with the EU treaties. Or that the UPC harmonises national laws with regard to direct and indirect infringements and limitations thereof, whereas this harmonisation takes place outside of the specific provision (Art. 114 TFEU) in the EU treaties to do so.

But, as said, this is not the place here to detail legal arguments. What should be born in mind is that both the unitary patent regulation and the UPC agreement won’t survive a review by the CJEU of their mere legality. There is no doubt any more. As soon as Gandalf has the opportunity to be involved, his powers will kill the unitary patent package.

What to do? Follow the hobbits

One could believe that, given the extreme fragility of the unitary patent package, there’s nothing any more to be done about it but to let Gandalf use his powers. This would be a terrible mistake. It is true that, now that the legislative stage is over, the CJEU is the last best safeguard against these unlawful legal instruments. But the unitary patent was legally wrong from the start and should already have been smashed by EU legislators, let alone never proposed by the Commission. Nevertheless, as we’ve just seen, the media hype has been too strong to sell the unitary patent as a long-awaited progress for the European Union. It cannot be denied that the deceiving communication from the dark forces of Mordor has successfully hidden that the content of the unitary patent package was just leading to the exact opposite: an increase in the fragmentation of the European patent system which without any doubt will hamper innovation, specifically for European SMEs, rather than encourage it. Therefore, there is still work to accomplish in order to reverse public perception of the unitary patent. We missed an army of activists to influence the legislative process. We have to step into every opportunity to raise awareness about what the unitary patent actually is. In a wider perspective, we have to gain support from every advocacy group fighting for fundamental freedoms in the informational society in order to uncompromisingly oppose software patents. Here are some clues for you to act.

One could believe that, given the extreme fragility of the unitary patent package, there’s nothing any more to be done about it but to let Gandalf use his powers. This would be a terrible mistake. It is true that, now that the legislative stage is over, the CJEU is the last best safeguard against these unlawful legal instruments. But the unitary patent was legally wrong from the start and should already have been smashed by EU legislators, let alone never proposed by the Commission. Nevertheless, as we’ve just seen, the media hype has been too strong to sell the unitary patent as a long-awaited progress for the European Union. It cannot be denied that the deceiving communication from the dark forces of Mordor has successfully hidden that the content of the unitary patent package was just leading to the exact opposite: an increase in the fragmentation of the European patent system which without any doubt will hamper innovation, specifically for European SMEs, rather than encourage it. Therefore, there is still work to accomplish in order to reverse public perception of the unitary patent. We missed an army of activists to influence the legislative process. We have to step into every opportunity to raise awareness about what the unitary patent actually is. In a wider perspective, we have to gain support from every advocacy group fighting for fundamental freedoms in the informational society in order to uncompromisingly oppose software patents. Here are some clues for you to act.

Finish the unitary patent package off

The first obvious thing to do is making sure that the unitary patent is permanently taken off the streets. All legal flaws should be collected together, with detailed legal arguments and references, in order not to leave a single doubt that the unitary patent package is illegal. Such a task is not too difficult given that arguments have been raised here and there, both about the unitary patent regulation and the UPC agreement.

The first obvious thing to do is making sure that the unitary patent is permanently taken off the streets. All legal flaws should be collected together, with detailed legal arguments and references, in order not to leave a single doubt that the unitary patent package is illegal. Such a task is not too difficult given that arguments have been raised here and there, both about the unitary patent regulation and the UPC agreement.

More difficult is the task of having such legal flaws reviewed by the CJEU. It is more than unlikely that the European Commission, the Council of EU, or the European Parliament brings any action. On the contrary, these EU bodies have deliberately done their best to pass illegal texts in the hope that illegalities they were aware of would be hidden enough to escape nullification. Given this, a referral to the CJEU can only be made by a Member State or by any individual or firm directly affected by a unitary patent or a litigation before the UPC. This second option would be the last chance for a solution. Indeed, it means that the unitary patent regulation has entered into force and that the UPC is installed and functioning. But if someone ever happened to be under threat before before the UPC, the best thing for her to do would be to raise as a defence the invalidity of the unitary patent regulation or of the UPC agreement.

Nevertheless, the best option would be for a Member State to attack the unitary patent package before its entry into force. Italy and Spain, having refused to join the enhanced cooperation in the first place, are of course the best candidates to bring such an action in invalidity. While Italy has shown some signs of eventually taking part in the UPC, Spain has even pledged to challenge the legality of the unitary patent regulation, would its first action against the enhanced cooperation procedure be rejected. Therefore, you are greatly encouraged to press on your national government to contest the validity of the unitary patent package before the CJEU, especially if you’re Spanish. But any government is able to do so. Your chance of success depends on your government’s acceptance of the unitary patent package – some countries are more reluctant than others, as we gonna see in a moment – and in the democratic influence allowed by your national constitution – some governments are strongly bound by decisions of their national parliament, whereas in some other Member States there is nearly no parliamentary influence. It should be noted that any government that would bring such an action in invalidity before the CJEU, not only would act in its own interests, but would actually protect any firm and individual from any EU Member State. Therefore any such action should be supported by every citizen and company.

Another opportunity for action lies with the ratification process of the UPC agreement, which is supposed to happen, in accordance with the constitution of each Contracting Member State, in the course of 2013. In Germany, the government has warned that an examination of its impact with regard to the German constitution has to be done. This should be the case for all Contracting Member States, but such a constitutional review by the Karlsruhe Court is particularly comprehensive. In Ireland, a referendum is mandatory, because of the transfer of judicial powers to an international body. In the United Kingdom, this very same condition could also trigger a referendum lock, enshrined in European Union Act 2011, let alone recent speculations about British citizens being consulted about the desirability for UK to stay in or leave the EU. In Denmark, the loss of sovereignty also requires approval by a referendum or by a 5/6 majority in the national Parliament, while an alliance between both left-wing and right-wing groups has declared that they will reject any potential agreement on the unitary patent. In Poland, based on a study by Deloitte, which shows that the unitary patent would be more costly to Polish companies than the current system, the Polish government has even refrained from signing the UPC agreement. It should be noted that the conclusion reached by the Polish government can be shared by any other country with a small patent activity – that is, all EU Member States but Germany, France, and to a lesser extent the United Kingdom and the Netherlands.

So in a lot of countries, the ratification process of the UPC agreement gives some opportunities to raise legal, political and economic inconsistencies that have been blindly accepted by the EU legislators. Then, how can you practically influence this process? Unfortunately, I don’t know of any magical weapon. But what I know is that the key to success lies with information. You have to spread information about the actual issues of the unitary patent package. Actual “Myths and Facts” have to be known.

For instance, since the adoption of the unitary patent regulation, more and more media reports and blog posts have welcomed this decision on the basis of the same myths, the origin of which can be traced back to EPO’s and the Commission’s Press Relations. Everybody celebrates that, after 30 years of failures – an alternative version of this myth dates the project from the 1960s – the EU has achieved a breakthrough by finally adopting a single patent for the internal market, which will be available in early 2014 and will provide a reduction in the cost for EU businesses of protecting their innovation, from 30 000€ as of today to 6 500€, and even 5 000€ after a transition period of at most 12 years, allowing Europe to catch up with the United States and China on the number of granted patents. Each time you see these myths, you should remind people of facts by posting comments on blogs, or writing the journalist.

You should remind them that stating the unitary patent package will enter into force in 2014 is no more than wishful thinking. Let alone current and future oppositions challenging its legality, the ratification process of the UPC agreement is likely to take more time. Moreover, according to Article 89 UPC, the UPC cannot enter into force before Brussels I regulation “on jurisdiction and the recognition and enforcement of judgments in civil and commercial matters” has been amended with specific provisions with regard to the UPC jurisdiction. Too bad, a recast of Brussels I regulation has just been voted by the EU Parliament and the Council (EU 1215/2012, and published in EU Official Journal of December 20th, 2012, L 351/1). But nothing about UPC was taken on board this recast, which was proposed two years ago. Therefore the Commission has to make another proposal which has to go through the EU legislative procedure. That is, neither the UPC agreement, nor the unitary patent regulation can enter into force before another amendment to Brussels I is voted by the European Parliament and the Council.

You should remind them that any assertion about costs is baseless since fees for the grant and renewal of a unitary patent are still unknown. And the EU won’t have any say about these fees, since it has decided to let them be decided by heads of national patent offices inside the Select Committee of the EPO. And UPC court fees are also unknown and will be decided by the same people in the UPC Administrative Committee. It should be noted that no cost-benefit study has been published since 2009, at a time when it was foreseen that the EU would be a party to the patent court and would provide funding. Nevertheless, a draft study from Commissioner BARNIER’s services, dated from November 2011, can be found on the Internet. But this study is very cautious, pointing out repeatedly that its proposals are “without prejudice to any future decision of the Administrative Committee”. Moreover it is based on assumptions that are no longer valid – for instance, the final choice to split the central division between Paris, Munich and London is likely to have an impact on the setting up of local or regional divisions in these countries; likewise, the transition period has been lengthened, increasing the likelihood for patentees to opt-out from the UPC jurisdiction. Anyway, even if estimations from this study were to be confirmed, the most important point to raise about UPC court fees is written in black and white: the “level of [UPC] court fees might be higher than in most Contracting Member States”. To put it differently, it will be more costly for most firms — with the possible exception of invalidity proceedings in Germany – to defend themselves against frivolous patent infringements. So if someone really wants to talk about the costs of the unitary patent, you should ask whether full costs – including fees for grant, renewal, prosecution, attorney, and not only for the patent holder but also costs to defend oneself in a patent litigation – are cheaper or more expensive than now. Even according to patent attorneys – see Kluwer Law International, KSNH Patentanwälte or Jochen Pagenberg – costs for European firms, and specially SMEs, are unfortunately expected to be much higher with the unitary patent and the UPC.

One more thing about the Commission’s study on the financing of the UPC. A copy is available on the website of the Ministry of Justice of the Slovak Republic. The source unveiled the author of the document: Eskil WAAGE. Eskil WAAGE is a lawyer who, according to a report from the Intellectual Property Lawyers’ Association about a patent experts meeting of 20 February 2009, has been seconded to DG MARKT from the EPO (DG5) for 2-4 years to help out with the current patent dossiers, with the approval of Alison Brimelow, but under the instructions of Margot Fröhlinger. Alison BRIMELAW was the president of the EPO at that time. Margot FRÖHLINGER was the director for intellectual property in the European Commission’s internal market and services department. She has been the main drafter of the unitary patent package. In April 2012, she left the Commission, and was appointed principal director for patent law and international affairs of the EPO. You should expose this incestuous relationship, and you should raise that the unitary patent package has been designed to a great extent by its first beneficiary: the EPO.

And you should also remind people, as detailed above, that the unitary patent is far from qyakifying as the long-awaited single EU patent. You should remind them of basic facts, such as the irrelevance of patents number to measure innovation – even patent lawyers feel “confounded as to how European politicians are able to state that the number of granted patents is directly proportional to the innovation of a country/jurisdiction, when we all know it is not”; or that European patents are granted mostly to non-EU firms; or that the patent system of the United States is currently facing a crisis, so aiming for the European patent system to catch up with its equivalent from the other side of the Atlantic is just a call for a future crisis.

On every aspect of the unitary patent and of the UPC, you should remind people of facts. You shouldn’t let the Commission and the EPO be the only sources of information. You should attend to “information” meetings and lectures that, without any doubt, many law firms will organise, and step up if the delivered information is incomplete or false. You should organise lectures to educate the public at large. On the unitary-patent.eu website, I've tried to give you detailed information, as accurately and completely as possible. All the arguments are there. All the facts. All the debunked myths. You should read them again, understand them, make them yours, rewrite them in your own wording. For instance, this article includes several silver bullets. But it is way too long. If you’re interested enough to have read this far, you should write a summary, take issues one by one and explain them simply. Make these issues be yours, and spread your understanding. This is the only way I can think of to influence opinion about the unitary patent.

Get rid of software patents

I’ve made one mistake during the legislative stage that led to the adoption of the unitary patent regulation. My mistake was to take for granted that the awareness on the dangers of software patents was already high enough and had been growing ever since the successful battle against the EU directive on software patents in the early years of the millennium. Obviously, this wasn’t the case. European activists, leave alone public opinion, have not realised that everything we have been warning against for ten years, with regard to the harmful consequences of allowing software patentability, is currently witnessed.

I’ve made one mistake during the legislative stage that led to the adoption of the unitary patent regulation. My mistake was to take for granted that the awareness on the dangers of software patents was already high enough and had been growing ever since the successful battle against the EU directive on software patents in the early years of the millennium. Obviously, this wasn’t the case. European activists, leave alone public opinion, have not realised that everything we have been warning against for ten years, with regard to the harmful consequences of allowing software patentability, is currently witnessed.

Software patents have been routinely filed and granted – both in the United States and in Europe – since the mid 80s or the early 90s. With a maximum lifetime of 20 years for a patent, this means that we are currently witnessing the end of the first generation of software patents. Therefore the damages they cause are no longer a matter of anticipation but of observation. And what can be observed is that software patents have now hit the headlines – at least in the United States. Why? Mainly because of the most obvious perverse effects they have generated: the rise of a new business model which is taking advantage of the flaws of the patent system to stifle productive businesses. I’m talking about “patent trolls”. These are for-profit entities which do not make any product, nor offer any service for sale. Rather they generate revenue by acquiring a patent portfolio that they use to force other companies to either buy a license from them, or be litigated. Over the last decade, it has been observed that patent trolls threatened to drive popular devices off the market, that even common day-to-day tasks like scanning a document to be sent by email were under threat, that every company running a website was a potential target, that victims included mostly SMEs, that the overall cost of patent trolls to the economy amounted to several tens of billions of dollars per year, that some patent trolls grew so big that even giant hi-tech companies preferred to finance them rather than being caught sooner or later into their nets, that some companies had even chosen to sell their own patents to some patent trolls in order for the latters to do the dirty work of collecting money from competitors, etc. So much trouble that even the President of the United States acknowledged the issue during a casual video debate. Another much observed consequence of software patents is how they are used as weapons in economic warfare. A war between big players, with deep pockets, who are now spending less money on research and development than on patents. A war with huge amounts at stake. The term “thermonuclear war” has been mentioned. And it has not escaped to anyone that the telecommunication industry was indeed a devastated field, to the detriment of consumers.

It is true that these damages caused by software patents are mostly occurring in the United States. Nevertheless, they are spreading more and more to European markets and courts. In any case, what has been proposed and accepted inside the unitary patent package is a clear step towards importing the same harm to this side of the Atlantic Ocean. Would unitary patents eventually be granted and enforced, software patents are likely to be as dangerous as they are in the US, if not more. It doesn’t matter that, given all the legal flaws in the unitary patent package, it is fortunately doomed to never come into existence. The abdication of the European political power to leave the European patent system be designed and governed by the sole patent microcosm is already extremely worrying. Since this treat has been underestimated, it is worth recalling why, before glancing at the darkness where all this is taking us.

There are three direct reasons why the threat of software patent would be exacerbated by the unitary patent package: the increase of powers for patents, the intensification of imbalances in favour of patentees, and the expansion of the level of autonomy for the patent microcosm.

By definition, patents under the unitary regime will have more power than today, since they will apply to the whole EU – except Spain and Italy and those countries which won’t ratify UPC – instead of a few countries. This means for instance that injunctions, which today forbid selling a computing product when found to infringe a software patent in a national market, will now expand to – almost – the whole EU. Think about rulings over some Apple computing patents that have banned some Samsung products from the Netherlands or Motorola products from Germany. Now, nearly the whole EU market will suffer from these injunctions. Moreover, if the claimed objective of the unitary patent regulation to ease the granting of patents in Europe is fulfilled, then this is likely to lead to an explosion of granted patents and litigations over bad quality patents, and especially software patents, granted by the EPO. This has been observed elsewhere and notably in the US: when there is an explosion in patent applications and granted patents, patent quality declines. And this is all the more true with regard to software patents.

As already noted, the unitary patent package is completely silent with regard to any usual countervailing rights in patent law, i.e. exceptions and limitations, prior user-rights, compulsory licenses, etc. But the imbalances in favour of patentees are also conspicuous in the structure of the Unified Patent Court (UPC) with regard to infringements. Cases of patent infringements would be allocated to a national or a regional division according to the country of residence of the alleged infringer or according to the country where the alleged infringement occurs, this at the choice of the patentee. This means that a patent holder who operates throughout the EU internal market would be able to choose the forum which is best suited to its needs. The defender could be forced to defend herself in a foreign language and under unfamiliar national patent law and patent traditions. This is the risk of “forum shopping” denounced notably by Ericsson, Nokia and BAE. Conversely, counterclaims for revocation – i.e. when a defender in an infringement case raises that the patent is actually invalid – can be either processed by the same local or regional division where the infringement case is pending, or forwarded to the central division. The local or regional division can rule on the infringement case without waiting for the ruling of the central division on the revocation case. This means that injunctions can be obtained for patent infringement even if the patent is later invalidated. Nokia has described this so-called “bifurcation procedure”, or “separation of invalidity and infringement proceedings”, which is the current German procedure, as a paradise for patent trolls. Worse, when the patent holder is not a party to the litigation, but when the action was brought by an exclusive licensee, then counterclaims for revocation are not allowed any more. It is known that patent trolls routinely create shell companies to bring legal actions. This feature of the UPC will open a huge window of opportunities for patent trolls, who mostly base their extortion business on software patents.

Finally, I have already stressed at large how the unitary patent system would be fully in the hands of the patent microcosm. Unitary patents would be granted by the EPO, a body installed by a non-EU international convention, fully outside of EU control, which has already granted hundreds of thousands of software patents. Renewal fees for unitary patents would be decided by a so-called “Select Committee” of the Administrative Council of the EPO, which would be mainly composed by heads of national patent offices. Since these fees would be redistributed between the EPO and national patent offices, according to decisions made by this same “Select Committee”, it is likely that EPO examiners would be pressured to grant more patents than to reject applications. Last year in 2012, EPO staff has even been rewarded for having done so. This is likely to lead to even more software patents granted. And the way the UPC would be staffed with judges also raises concerns. The UPC would include an “Advisory Committee” comprising patent judges and practitioners in patent law and patent litigation, and an “Administrative Committee” with representatives of Contracting States. Governments are likely to appoint heads of their national patent office to this Administrative Committee, as tgey do for the Administrative Council of the EPO, . Judges of the UPC would be appointed by the Administrative Committee on the basis of a list established by the Advisory Committee. This means that judges of the UPC, who would have exclusivity with regard to patent litigations throughout Europe, would be chosen by patent offices, judges and lawyers, i.e. by the patent microcosm. As already mentioned, the UPC would include some engineers, as technical judges. But it is still unknown whether computer scientists would be selected as technical judges. What is known is that the European Parliament and the Council, contrary to some previous versions, have finally chosen not to include any provision preventing members of the EPO to be judges at the UPC. No need to explain the implications of such an exceptional jurisdiction for the enforcement of software patents. As in the US, patent law would be made more by the patent microcosm than by legislators. But contrary to the US, given that no substantial patent issues would be referred to it, the CJEU wouldn’t be able to play over the UPC even the minimal safeguarding role which the US Supreme Court pays towards the CAFC.

I guess it is clear now that, with the unitary patent package, Europe would experience no less harm from software patents, possibly more, than the United States. I’m not saying that it was the goal of the unitary patent package to make software patents legally enforceable in Europe – hobbits are not really found of conspiracy theories. Nevertheless, it was known from the start that proponents of software patentability would try to achieve their goal through the unified patent court project. And the European Commission, the Council of the EU and the European Parliament, singly and together, have let this happen. This is not only a shame, but a clear surrender to the dark forces of Mordor!

Because it is a current reality that everything done with software can be and is patented. There are software patents not only on algorithms, but also on protocols, on computing languages, on file formats, etc. This means that everything that can be performed with software could depend on the will of thousands and thousands of patent holders for actual implementation. Everything! Free Internet? Forget it! Forget the Internet altogether. Because any software used to access the Internet, any software to run servers, any routing device, any communication protocol, any data format for any exchanged information, anything will depend on the will of thousands and thousands of patent holders. Business methods are surely the most well-known application of software patents. But, since software is just a way to represent and process symbols, any intellectual method can be implemented in software, and therefore be expropriated by patent holders. Educational methods, entertainment methods, medical diagnosis methods, etc.

To conclude, let’s make some prospects – hobbits love science-fiction! I’m convinced that sooner or later writing software will become a natural way to speak for most people. Sooner or later software will be a popular genuine means of expression. Sooner or later people will interact with each other by software means. This won’t happen with software patents! Because to make it happen, we cannot afford to be dependent on the will of thousands and thousands – millions at that time – of patent holders. We need free creativity. And this is why I believe that the fight against software patents is one of the most important fights to engage into. And, in Europe, this fight means that the unitary patent package must be defeated.